Linsenrasterfotografie / Lenticular screen photography

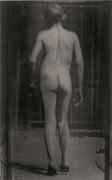

Mit den Linsenraster-Fotografien nimmt Schilling Bezug auf die Chronofotogarfien von Eadweard Muybridge und Étienne-Jules Marey in den 80er Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts. Während Muybridge in einem Bild verschiedene Standpunkte einer Momentaufnahme zeitgleich darstellte, integrierte Marey eine Serie von Bewegungsaufnahmen in einem Bild. Beide Aspekte behandelt auch Alfons Schilling, wenn er einerseits in einem Bild bis zu 30 verschiedene Ansichten zeigt oder auch in einem Bild die einzelnen Bildphasen eines Bewegungsablaufs sichtbar macht. Der Künstler-Ingenieur Alfons Schilling entwickelte selbst eigene Verfahren und Geräte für die Aufnahmen der 3D-integral fotografischen Bilder als auch das Linsenrastersystem.

Martina Tritthart. Alfons Schilling – Wahrnehmungsapparate. "Wieviel man heute noch sehen kann, ist wirklich zweifelhaft", 2011

Carl Aigner: Apparative Blicke

Photomediale Strategien in den Linsenrasterbildern von Alfons Schilling

Aus: Alfons Schilling. Ich / Auge / Welt. The Art of Vision. Springer-Verlag. Wien, New York, 1997. S. 53-57

„Wieviel man heute noch sehen kann, ist wirklich zweifelhaft.“

Alfons Schilling

Seit den sechziger Jahren interessiert sich Alfons Schilling für Raum-, Bild und Bewegungsinformationen und Möglichkeiten neuer Bildstrategien. Gemeinsam mit dem Wissenschaftler Don White führte er 1967 Untersuchungen zum neuen Medium Holografie durch und entwickelte kurze Zeit später eigene Stereosysteme, um seine Recherchen über das Verhältnis von Raum, Bild und Bewegung weiter vorantreiben zu können.

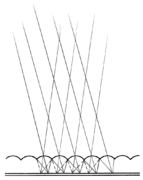

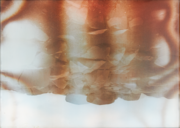

Angeregt durch Funde von banalen 3D-Kitschpostkarten, begann Alfons Schilling 1968 in Amerika mit seinen ersten fotographischen Experimenten mit dem „Lippmann-Linsen-Raster“. Dieses Linsenrastersystem besteht aus einem transparenten Plastikmaterial, dessen Oberfläche aus langgestreckten halbzylindrischen Linsen geformt ist. In Kontakt mit dem Fotopapier können durch diese Anordnung je nach Winkel bis zu 30 verschiedene Bilder in einem einzigen Bild optisch „gespeichert“ werden. Diese Komprimierung visueller Informationen gelang ihm mit Hilfe speziell entwickelter Apparate und unter großen technischen Schwierigkeiten.

Von Beginn an faszinierte Schilling dabei das Moment der multiplen Information in einem derartigen (fotographischen) Bild, welches für ihn zu einem wichtigen Modell des lntegralbildes schlechthin wurde. Er versteht darunter die Möglichkeit, in einem Bild eine Vielzahl anderer Bilder technisch zu integrieren und diese bei der Betrachtung wieder einzeln sichtbar werden zu lassen. Dabei geht es ihm weniger um realistische Darstellungsstrategien, als vielmehr um die Frage nach dem tatsächlich Räumlichen, genauer: nach dem Verhältnis von Raum, Bild und Bewegung mit all den inversiven Möglichkeiten, wie er sie zum Beispiel mit dem „Raumumkehrer“ 1974 entwickelte.

Bei diesen foto-optischen Komprimierungen qua Linsenraster spielt der Betrachter eine rezeptiv-dynamische Rolle:

„Der Betrachter aktiviert das Bild, er ist es, der das Bewegungsbild in Aktion bringt. Er bewegt sich, um das Bild in Bewegung zu bringen, das Bild bewegt sich mit. Durch einen Schritt kann er die gesamte Bilderwand in Bewegung bringen, es wird erst durch ihn zu dem, was es ist. Diese Gegenseitigkeit hat mich damals äußerst interessiert, weil es vom Betrachter ein neues „Sehen“ verlangt. Mein Werk wird sozusagen von ihm beendet. Bei den Raumfotos ist es noch schwieriger, weil der Schauende die Positionen im Raum suchen muss, von denen das Bild räumlich gesehen wird.“[1]

So beschreibt Alfons Schilling selbst jene dezisiven, für ihn relevanten Aspekte der Linsenrasterfotografien, die einen immens avancierten pikturalen Diskurs darstellen, insoferne mehrere Betrachter je nach Blickpunkt der Bildwahrnehmung jeweils auch verschiedene Bilder simultan in einem Bild sehen können.

Schillings Faible für technisch-visuelle Experimente knüpft bei den Linsenrasterbildern am wichtigsten Wahrnehmungsmodul seit der Renaissance, dem zentralperspektivischen Blick, an, den er durch die Geschwindigkeit des Kamerablicks perfektioniert sieht. Seine Aufmerksamkeit gegenüber diesem ersten apparativen Bildmedium in der Geschichte der Bilder gilt also dessen medialen Qualitäten. In der Tat stellt das fotografische Bild eine veritable Revolution des Bildes dar, ist ein eminenter Bilderbruch[2], der fast alle bis zur (Er-)Findung der Fotografie gültigen Bildparameter radikal aufzulösen begann und einen neuen Status des Bildes begründete. Dies betrifft sowohl den Bild-, Werk-, Kunst- und Künstlerbegriff als auch das Verhältnis von bildexterner und bildinterner Information, also der Relation von Bild und visueller Wirklichkeit.

Die fotografischen Strategien der lntegralbilder beziehen sich also nicht auf das neue Abbildungsdispositiv der Fotografie, sondern auf deren Vermögen der Begründung neuer Wahrnehmungsmodule, wie wir sie in den Bewegungsphotographien von Eadweard Muybridge und Etienne-Jules Marey kennen, die sie in den achtziger Jahren des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts entwickelten. Dies tangiert unmittelbar die neue optische Raumdarstellungsqualität des fotografischen Bildes in Bezug auf Bewegung und Zeit. Muybridge entwickelte seine fotografischen Bewegungsanalysen in Form serieller Einzelbildreihungen, die zeitgleich ein Objekt aus drei verschiedenen grafischen Grundlagen schuf, während Marey die chronofotografischen Grundlagen schuff, indem er mehrere Bewegungsaufnahmen in ein Bild integrierte. Gerade die Arbeiten von Muybridge und Marey ergaben für Schilling einen neuen Schlüssel im Raum-Bild-Bewegungsbezug, da die Fotografie damit als analytische Sehmaschine konstituiert wurde: ..Ich glaube", so formulierte es Schilling in einem Interview 1985, ..das nackte Auge ist tatsächlich an seinem Ende angelangt, es ist immun geworden.“[3] Indem er die Bildwahrnehmung nicht als passiven Akt setzt, sondern als einen interaktiven Wahrnehmungsprozess, der wesentlich durch den Betrachter und dessen Bewegung konstituiert wird, suspendiert Schilling alle traditionellen Vorstellungen vom Bild, da er den Betrachter selbst als integralen Teil des Bildes begreift.

Die Bündelung von multipler visuell-fotografischer Information, Bewegung und Räumlichkeit wird durch die „Art of Vision“ von Alfons Schilling im Untertitel der vorliegenden Publikation erkenntnistheoretisch konkretisiert: Ich-Auge-Welt. Diese epistemische Triade zieht sich durch eine Reihe von wahrnehmungstheoretischen Schriften seit der Renaissance, insbesondere seit Leibnitz' Schriften, die in der Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit nicht nur das Subjekt neu begründet (cogito ergo sum), sondern es auch mit dem immer mehr vorherrschenden Status des Sehens als video ergo sum paraphrasieren ließe. Die apparative Mediatisierung der Blicke seit dem 19. Jahrhundert gerade durch die Fotografie macht dieses Medium zu einem Fokus wahrnehmungstheoretischer Überlegungen des Künstlers. Geht man davon aus, dass sich der Begriff des Bildes und der des Subjekts in der okzidentalen Kultur- und Kunstgeschichte eng verknüpfen lässt[4], so wird dies auch im gesamten Œuvre von Schilling sicht- und einsehbar, insbesondere in der fotografischen Passage seiner Arbeiten. Es war bis zur Erfindung des Kinos und des digitalen Bildes speziell das fotografische Bild, welches die Frage nach dem Subjekt im Angesicht eines fundamental neuen Bildes (sowohl, was seine Materialität, als auch, was seinen Produktionsstatus betrifft) erneut aufwarf. Antiromantisch in seiner Grundkonzeption, massenmedial in seinem apparativen Status kokonstitutionierte es auch das Subjekt neu: „In der Fantasie stellt die FOTOGRAFIE (die, welche ich im Sinn habe) jenen äußerst subtilen Moment dar, in dem ich eigentlich weder Subjekt noch Objekt, sondern vielmehr ein Subjekt bin, das sich Objekt werden fühlt“.[5]

Was Roland Barthes hier anspricht, findet sich – welch aufschlussreiche Parallelität – in der Subjektdiskussion der 70er und 80er Jahre wieder: vom multiplen Bild zur multiplen Persönlichkeit. Alfons Schilling spürt genau diesen parallelen Entwicklungen von Bild und Subjekt nach, wenn er, ausgehend vom fotografischen Bild, die Perzeption in ihrer Verschränkung von Bild und Apparat, von Ich, Auge und Welt in das Zentrum seiner künstlerischen Laboratorien stellt, ganz einfach auch dadurch, dass er die Fotografie nicht als Abbildung, sondern als Herausbildung begreift, als ein Instrument der analytischen Perzeption:

„Es wäre eben wichtig, dass das menschliche Auge abgewertet wird, dass ihm seine Einmaligkeit genommen wird, dass es gesehen wird als eine der vielen Möglichkeiten. Das könnte die Voraussetzung schaffen für ein neues ‚Bild‘.“[6]

Alfons Schilling geht es nicht um die Affirmation von bestimmten Bilddispositiven, wie sie sich seit der Renaissance konstituieren konnten, sondern um deren Transgression und Transformation. In infografischer Hinsicht untersucht und reflektiert er das Zeitalter der „paradoxen Logik“ des Bildes[7], das durch das Ende der Strategie der Repräsentation gekennzeichnet ist. Dabei ist für Schilling signifikant, dass er die Relation von Bild und Blick ins Zentrum seiner künstlerischen Aufmerksamkeit rückt, wenn es um die Frage nach der Möglichkeit neuer Bilder geht. Mit den apparativen Bildern wird der Begriff der Sehmaschine virulent: die Bilder selbst avancieren zu Sehmaschinen, die den Blick ko-konstituieren. Auch diesbezüglich wird die Fotografie zu einem Wahrnehmungskatalysator, nicht nur, weil sie das Bild als Fragment zu konstituieren begann, sondern weil sie auch die differente Relation zwischen Bild und bildexterner Wirklichkeit zum Verschwinden bringt: Blick, Bild und Wirklichkeit kollidieren. Aus diesen Bilderfahrungen heraus [Virilio spricht vom Zeitalter der dialektischen Logik der Bilder, siehe Fußnote] wird die „Göttlichkeit“ des Auges selbst brüchig und zu einem Nicht-Blick : „Im Mittelpunkt des Dispositivs der künftigen ‚Sehmaschine‘ steht also die Blindheit, denn die Produktion eines Sehens ohne Blick ist selbst nur die Reproduktion einer intensiven Blindheit, einer Blindheit, die zu einer neuen letzten Form von Industrialisierung wird: der Industrialisierung des Nicht-Blickes.“[8]

Alfons Schilling spürt diesem Nicht-Blick seit den 60er Jahren nach und kann in diesem Zusammenhang von der notwendigen Abwertung des menschlichen Auges sprechen, davon, dass ihm seine Einmaligkeit genommen werden muss, um adäquatere Bildfindungen zu ermöglichen.

[1] Zitat aus einem unveröffentlichten Manuskript von Alfons Schilling, o. J.

[2] Vgl. dazu Paul Virilio: Die Sehmaschine, Berlin 1989, sowie Carl Aigner: „Bilderbuch. Pikturale Strategien der Vermessenheit“, in: Margot Pilz: Die Auflösung der Fotografie – Der kalte Raum, Ausstellungskatalog NÖ. Landesmuseum, Blau-Gelbe Galerie, Wien 1992, o. P.

[3] „Mit dem Kopf durch die Leinwand.“ Christian Reder im Gespräch mit Alfons Schilling, Falter 20/1985.

[4] Vgl. Peter Weibel: Die Beschleunigung der Bilder in der Chronokratie, Bern 1987; Gerard Simon: Der Blick, das Sein und die Erscheinung in der antiken Optik, München 1992; weiters: Jonathan Crary: Techniken des Betrachters. Sehen und Moderne im 19. Jahrhundert, Berlin 1996.

[5] Roland Barthes: Die helle Kammer. Bemerkungen zur Photographie, Frankfurt a. M. 1985, S. 22.

[6] „Mit dem Kopf durch die Leinwand“ Falter 20/1985.

[7] Paul Virilio: Die Sehmaschine, S. 144.

Carl Aigner: MACHINIC GAZES.

Photo-media strategies in the lenticulars of Alfons Schilling

From: Alfons Schilling. Ich / Auge / Welt. The Art of Vision. Springer Verlag. Wien, New York,1997. pp. 53-57

“It is really doubtful how much you actually can still see today.”

Alfons Schilling

Ever since the 1960s, Alfons Schilling had been interested in space, image and motion, and in possibilities of new visual strategies. Together with scientist Don White, he conducted examinations about the new medium of holography in 1967, and not long after that was developing his own stereoscopic systems to push on with his research of the relationship of space, time, and motion.

Inspired by banal 3D kitsch postcards he came across, Alfons Schilling started his first photographic experiments in America in 1968, using the “Lippmann lenticular screen.” This lenticular screen system consists of a transparent plastic sheet with a surface shaped into elongated half-cylindrical lenses. Placed on top of a specially prepared photo paper, this structure enables, depending on viewing angle, up to thirty different images to be optically “stored” in a single one. He was able to achieve this compression of visual information with the help of specially developed devices and with great technical difficulty.

From the very beginning, Schilling was fascinated by the idea of multiple information being contained in such a (photographic) image, which, for him, became an important model for the integral image per se. By this he understands the possibility of technically integrating a variety of images in a single one and making them visible again individually in the viewing process. For him, this is not so much about strategies of realistic representation, but rather about the issue of actual spatiality, more precisely, of the relationship of space, time, and motion with all the possibilities of inversion, as implemented, for example, in the “Space Inverter” of 1974.

In such photo-optical compressions by lenticular screen, the viewer plays a receptive-dynamic role:

“The viewer activates the image, it is he who puts the motional picture into action. He moves to set the image in motion, the image moves along. With just one step, he is able to set an entire image wall in motion, it is through him that it becomes what it is. This reciprocity is what I was highly interested in at the time, because it requires a new ‘vision’ of the viewer. My work is, so to speak, completed by him. In the spatial photos, it is even more difficult, because the viewer first needs to find the position in the room from which the image is seen as three-dimensional.”[1]

This is how Alfons Schilling himself describes those decisive aspects of lenticular photographs, which were most relevant for him and which present an immensely advanced pictorial discourse insofar as they allow for several viewers, depending on their respective viewpoints, to see different images simultaneously in one picture.

Schilling’s penchant for technical-visual experimentation picks up, in the case of lenticular images, on the most crucial module of perception since the Renaissance period, central perspective, which he sees perfected by the sheer speed of camera vision. His attention to this earliest machinic visual medium in the history of images thus focuses on its media qualities. The photographic image indeed represents a revolution of the image, it is an eminent pictorial disruption[2] that began to radically erode nearly all picture parameters that had been in effect up until the invention of photography and established a new status of the image. This has an effect on the notions of picture, work, art, and artist as well as on the relationship of image-internal and image-external information, that is, on the relation of picture and visual reality.

The photographic strategies of integral images therefore do not relate to the representational dispositif of photography but rather to its capacity for establishing new modules of perception as we have seen in the motion photographs of Eadweard Muybridge und Etienne-Jules Marey, which they developed during the 1890s. This immediately touches upon the new optical space-representing quality of the photographic image in relation to motion and time. Muybridge developed his photographic motion analyses in the form of serial sequences of single images, which created an object from three different graphic foundations at once, while Marey created the chronophotographic basics by integrating several different motion shots in one image. It was precisely the works of Muybridge und Marey that gave Schilling a new key to the space-image-motion relationship, constituting photography as an analytic vision machine: “I think,” as Schilling put it in an interview in 1985, “that the naked eye has really come to its end, is has become immune.”[3] By taking image perception to be not a passive act, but an interactive perceptual process essentially constituted by the viewer and his movement, Schilling suspends all traditional notions of the image in that he understands the viewer to be an integral part of it.

The bundling of multiple visual-photographic information, motion, and spatiality is concretized in epistemological terms by Alfons Schilling in the “Art of Vision” as stated in the subtitle of this publication: Self-Eye-World. This epistemic triad runs through a whole series of writings on perception theory ever since the Renaissance period, in particular since the writings of Leibnitz, which have not only reconstituted the subject in the cultural history of the Modern Age (cogito ergo sum) but also made it paraphrasable, in line with the increasingly prevalent mode of vision, in terms of video ergo sum. The machinic mediatization of vision brought about especially by photography since the 19th century made this medium the focus of the artist’s considerations on perception theory. The underlying assumption that a close link can be established between the notions of the image and the subject in occidental cultural and art history[4] also becomes visible and understandable throughout the whole of Schilling’s oeuvre, particularly in the photographic section of his work. Up until the invention of cinema and the digital image, it was especially the photographic image that re-addressed the question of the subject against the background of a fundamentally new image (with respect to both its materiality and production status). Antiromantic in basic concept, a mass medium in its machinic status, it also co-reconstituted the subject: “In a certain sense, the image-repertoire, the Photograph (the one I intend) represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object.”[5]

What Roland Barthes is referring to here is found again—in what really is an insightful parallelism—in the subject discussion of the 1970s and ’80s: from the multiple image to the multiple personality. Alfons Schilling traces precisely those parallel developments of image and subject when he, starting out from the photographic image, made perception and the way it interlocks image and apparatus, self, eye, and world, the center of his artistic laboratories, also simply by seeing photography not as a depiction but an articulation, an instrument of analytic perception:

“It would be important to downgrade the human eye, to strip it of its unique status, to view it as just one of many possibilities. This could provide the precondition for a new ‘image.’”[6]

For Alfons Schilling, the point in question is not affirmation of certain image dispositifs, as had established themselves ever since the Renaissance period, but about their transgression and transformation. From an infographic perspective, he examines and reflects the age of the “paradoxical logic” of the image[7], which is characterized by the end of the strategy of representation. What is significant for Schilling in this is to move the relationship of image and gaze to the center of his artistic attention when it comes to the question of the possibility of new images. With the machinic images, the notion of the vision machine becomes operative: the images themselves evolve into vision machines that co-constitute the gaze. This is yet another way in which photography becomes a catalyst of perception, not only because it began to constitute the image as a fragment, but because it makes the differential relation between image and external reality disappear: gaze, image, and reality collide. Such pictorial experience [Virilio speaks of the age of the dialectic logic of images, see footnote] makes the “divinity” of the eye turn fragile and into a non-gaze: “Blindness is thus very much at the heart of the coming ‘vision machine’. The production of sightless vision is itself merely the reproduction of an intense blindness that will become the latest and last form of industrialisation: the industrialisation of the non-gaze.”[8]

Alfons Schilling has traced this non-gaze ever since the 1960s, and in this context has come to speak of the necessary downgrading the human eye, of the need of stripping it of its unique status to clear the path to more adequate pictorial inventions.

Translation: Michael Strand, Vienna

[1] Quote from an unpublished manuscript by Alfons Schilling, n.d.

[2] Cf. on this Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (London, Bloomington, In., 1994), as well as Carl Aigner: “Bilderbuch. Pikturale Strategien der Vermessenheit,” in Margot Pilz, Die Auflösung der Fotografie – Der kalte Raum, exh. cat. NÖ. Landesmuseum, Blau-Gelbe Galerie (Vienna, 1992), n.p.

[3] “‘Mit dem Kopf durch die Leinwand.’ Christian Reder im Gespräch mit Alfons Schilling,” Falter 20 (1985). Available online at http://www.christianreder.net/archiv/b_97_schilling_visio.html.

[4] Cf. Peter Weibel: Die Beschleunigung der Bilder in der Chronokratie (Berne, 1987); Gerard Simon: Der Blick, das Sein und die Erscheinung in der antiken Optik (Munich, 1992); Jonathan Crary: Techniken des Betrachters. Sehen und Moderne im 19. Jahrhundert (Berlin, 1996).

[5] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York, 1982), p.14.

[6] See n. 3.

[7] Virilio, Vision Machine, p. 30.

[8] Ibid., pp. 72 f.